The Prevention Path Forward: What We Have Learned and What Is Next

- APSI

- Aug 20, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2025

Part 2 - The Rise of Prevention Science[1]

[1] Part 1 - How Treatment Shaped the Prevention Landscape; Part 3-Rethinking Risk: The Evolution of Harm Reduction; Part 4-What Is Next in Prevention: Research, Practice and Action

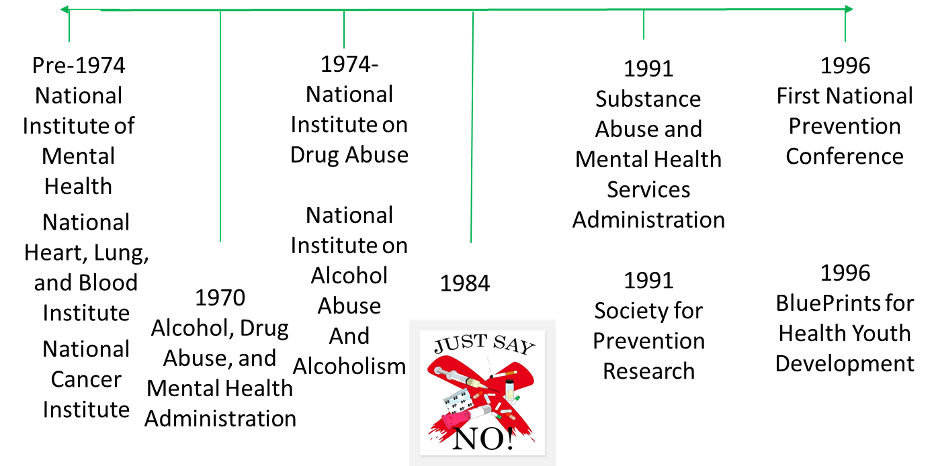

The history of substance use prevention is much shorter than that of substance use treatment even considering that the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention created by President Nixon in 1971 included Prevention in the title. At that time, prevention was synonymous with treatment. As one can see from the time-line below, recognition of drug use as an important health issue was not ‘officially’ recognized until 1974 with the creation of the National Institutes on Drug Abuse and Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism that, along with the National Institute of Mental Health were all incorporated into the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Services Administration.

Several significant events served to highlight the factors associated with substance use and the effectiveness of prevention of not only substance use but also other behaviors such as bullying and academic failure (e.g., Pentz et al., 1989; Botvin et al., 1990, Hawkins et al., 1992). In the 1970s through the 1990s, the National Institute on Drug Abuse supported longitudinal studies (Brooks et al., 1982; Kandel et al., Newcomb et al., 1987) that followed cohorts of children through adolescence and, in one case (Brooks et al., 2015) into late adulthood. Some of these studies included general populations mostly students in school and examined psycho-social factors including family relationships, engagement in risky behaviors, attitudes towards substance use, peer relationships, academic experiences. Other studies selected the children of substance users and not only collected similar psycho-social information but also conducted genetic testing. These studies sometimes included twins or other siblings or other children whose parents were not substance users.

The graphic shown here summarizes the findings from the etiological research published int the reference cited here (Fishbein and Sloboda, 2023). The model shows the interactions between the individual and that individual’s characteristics including his/her genetic makeup and history, temperament, and developmental achievements that make up what knowledge that individual has attained and how attitudes and beliefs are formed and norms perceived all the factors that influence behavior. Behavioral risk as well as protection is then the result of the interaction of these influences. Sociologists and other behavioral scientists reference this process as socialization, i.e. how individuals learn and internalize social norms, values, and behaviors through interactions with others and society. Key socialization sources/agents include parents and other family members, personnel associated with school/faith-based organizations and other key institutions, peers, work colleagues, social groups, children, grand-children, etc.. It is important to underscore that socialization is a continuous process across one’s lifespan offering opportunities to reverse negative trajectories (Kellam et al., 1975). Socialization is a key concept for prevention practice whereby prevention professionals teach and train key socialization agents through parenting or teacher management programs but prevention professionals are themselves socialization agents when they directly deliver an evidence-based prevention program to children.

The advances made in the late 1980s and through the 1990s in the development of prevention programs that demonstrated significant positive outcomes came the recognition of the key elements of prevention programming. The Blueprints for Violence Prevention was established in 1996 to provide a summary of programs that were found to not only be effective for violence but also drug use and in 1997, the National Institute on Drug Abuse published a summary of these advances in Preventing Drug Use Among Children and Adolescents—A Research-Based Guide as prevention principles (Sloboda and David, 1997). These principles were updated in 2011 (Robertson, David, and Rao) and cover the areas of risk factors and protective factors, prevention planning (for families, in schools, and community), and prevention program delivery.

And, in 2013 the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the World Health Organization published the International Standards for Drug Use Prevention that summarized the advances made in effective prevention strategies across age group and settings. This work was updated in 2018. Up to date, the Standards have advanced the prevention field by:

Establishing a shared global language for evidence-based prevention

Providing benchmarks for program quality and effectiveness to guide investment

Encouraging integration of prevention into broader health and development agendas

Serving as a training and advocacy tool for prevention professionals

Based on this history, in 2013 Applied Prevention Science International with funding from the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Narcotics and Law Enforcement, developed the Universal Prevention Curriculum that forms the basis of the current curriculum, Foundations of Prevention Science and Practice. Building on this history, in 2013 Applied Prevention Science International, with funding from the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Narcotics and Law Enforcement, developed the Universal Prevention Curriculum (UPC), which now forms the basis of the Foundations of Prevention Science and Practice. Designed to translate decades of research into practical application, the Foundations curriculum:

Reflects the latest scientific evidence in prevention

Builds core competencies for planning, implementing, and evaluating interventions

Emphasizes cultural relevance and ethical practice

Is continually updated to integrate emerging research, evolving global standards, and practitioner feedback

Strengthens capacity to sustain prevention systems over time

The Foundations training offers a common platform of knowledge and skills that supports high-quality prevention in any context. Whether new to the field or a seasoned professional, completing the Foundations training is an investment in delivering prevention that is effective, current, and built to last.

Although, there are no recent studies of the delivery of effective prevention programming across the United States, research from the early 2000s indicates that, like evidence-based treatment less than 50% of schools support the delivery of evidence-based prevention programming (Ringwalt et al., 2011; Sloboda et al., 2008).

References

Botvin, G.J., Baker, E., Dusenbury, L., Tortu, S. & Botvin, E.M. (1990). Preventing adolescent drug abuse through a multimodal cognitive-behavioral approach: results of a 3-year study. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 58(4), 437-46. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.437. PMID: 2212181.

Brook, J. S., Whiteman, M., & Gordon, A. S. (1982). Qualitative and quantitative aspects of adolescent drug use: interplay of personality, family, and peer correlates. Psychological Reports, 51(3_suppl), 1151-1163. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1982.51.3f.1151.

Brook, J.S., Balka, E.B., Zhang, C., & Brook, D.W. (2015). Intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1;24(10):2957-2965. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-0099-x. Epub 2014 Dec 18. PMID: 26512195; PMCID: PMC4620054.

Fishbein, D. H. & Sloboda, Z. (2023). A national strategy for preventing substance and opioid use disorders through evidence-based prevention programming that fosters healthy outcomes in our youth. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Reviews. 26:1–16.

Glantz, M. D., and Pickens, R. W. (Eds.). (1992). Vulnerability to drug abuse. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

Hawkins, J.D., Catalano, .RF. & Miller, J.Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1):64-105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. PMID: 1529040.

Hurd, Y.L., Manzoni, O.J., Pletnikov, M.V., Lee, F.S., Bhattacharyya, S. & Melis, M. (2019). Cannabis and the developing brain: Insights into its long-lasting effects. Journal of Neuroscience, 39(42):8250-8258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1165-19.2019.

Kellam, S.G., Branch, J.D., Agrawal, K.C., & Ensminger, M.E. (1975). Mental health and going to school. The Woodlawn program of assessment, early intervention and evaluation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Chicago Press.

Newcomb, M.D., Maddahian, E., Skager, R. & Bentler, P.M. (1987). Substance abuse and psychosocial risk factors among teenagers: associations with sex, age, ethnicity, and type of school. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 13(4):413-33. doi: 10.3109/00952998709001525. PMID: 3687899.

Pentz, M.A., MacKinnon, D.P., Flay, B.R., Hansen, W.B., Johnson, C.A. & Dwyer, J.H. (1989). Primary prevention of chronic diseases in adolescence: effects of the Midwestern Prevention Project on tobacco use. American Journal of Epidemiology, 130(4), 713-724. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115393. PMID: 2788994.

Ringwalt, C., Vincus, A.A., Hanley, S. et al. (2011). The Prevalence of Evidence-based Drug Use Prevention Curricula in U.S. Middle Schools in 2008. Prevention Science, 12, 63–69.

Robertson, E.B., David, S.L., & Rao, S.A. (2003). Preventing Drug Use Among Children and Adolescents: A Research-Based Guide, National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH Publication No. 04-4212(B).

Sloboda, Z. & David, S.L. (1997). Preventing Drug Use Among Children and Adolescents: A Research-Based Guide, National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH Publication No. 99-4212.

Sloboda, Z., Pyakuryal, A., Stephens, P.C., Teasdale, B., Forrest, D., Stephens, R.C., & Grey, S.F. (2008). Reports of substance abuse prevention programming available in schools. Prevention Science, 9(4), 276-287.

Comments